Spectacle

Author

Alex Tingiris

Date Published

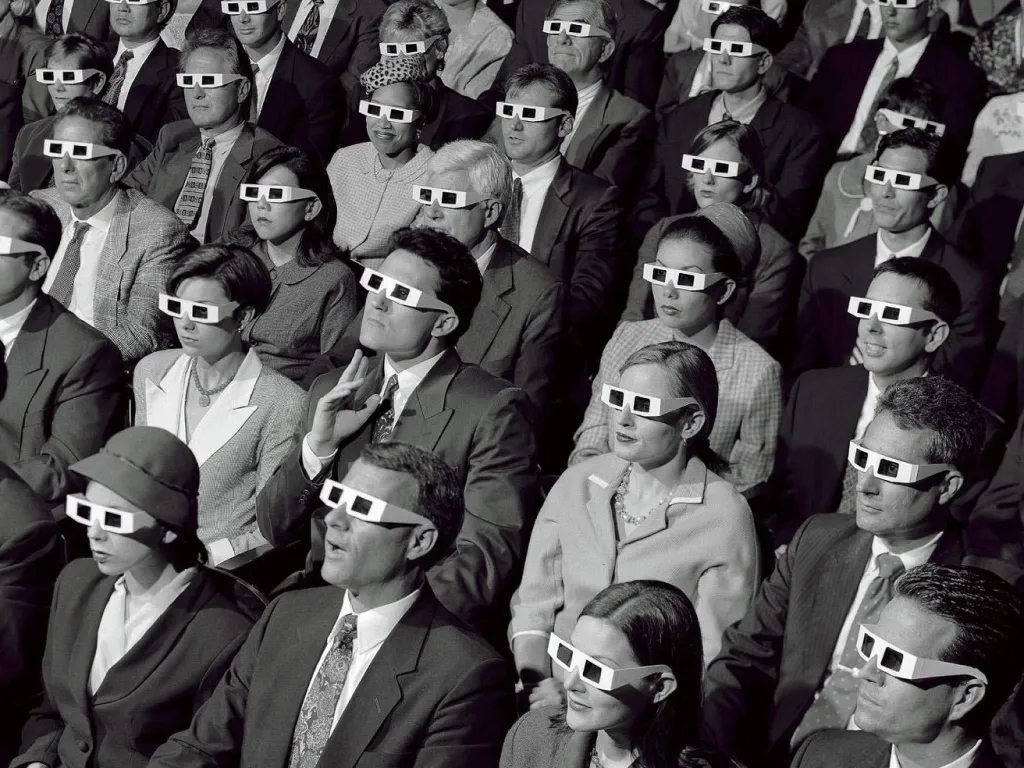

My first year of college, I took an art history class on 1960s counterculture. One of the many ideas that has stuck with me since was that of the “spectacle.” The term originated from Guy Debord, a French theorist and founding member of the Situationist International, in his 1967 book, The Society of the Spectacle. The spectacle refers to the way modern society uses mass media, advertising, and consumer culture to construct and maintain social control, alienation, and passivity.

In 2025, our lives are more intertwined with the spectacle than ever. Social media platforms are prime examples, where users curate idealized versions of their lives, often prioritizing image over reality. Ads promote lifestyles and desires, replacing genuine human needs with commodified substitutes. Spectacles in sports, politics, and entertainment distract from structural inequalities and systemic problems by focusing on trivial or dramatized content.

People are not incapable of breaking away from the norms of the spectacle, but doing so requires personal awareness that can be challenging to cultivate. For many, engaging in the necessary self-reflection is difficult due to time constraints and the rational tendency to delegate thinking to others. To have a rigorously considered opinion on every topic is impossible. The Danish theologian Søren Kierkegaard defended his commitment to Christianity against existentialist rationality by emphasizing the necessity of “faith”—assumptions or beliefs beyond our capacity for rational knowledge. I’m not religious, but Kierkegaard’s point resonates: everyone must place trust in things beyond their ability to rigorously understand.

A crucial aspect of Kierkegaard’s writing on faith is his rejection of imposing these irrational assumptions on others. Everyone’s experiences lead to different beliefs, and the only way to make people conform to a singular perspective is to force them to pretend alignment. The subjectivity of leaps of faith makes them impossible to genuinely apply to groups, organizations, or societal institutions. Faith is not objective, and treating it as such undermines its authenticity.

At 24 years old, I’ve found that little feels different from when I was 16, except I’ve become clearer about who I am, what I believe, and what I value. This clarity has only developed over time, through freedom and resources to explore, experience, and reflect. The more a culture restricts this exploration, the more it builds a less genuine, less confident, and less stable society. Reality is always more nuanced and less definable than it appears, which ensures the spectacle remains alive and well.

At Western Symbolics, we’re still in the early stages, with limited empirical evidence that our innovation process works. Much of what we’re doing operates on faith—rooted in my decade of building software and my family’s entrepreneurial background. Our primary objective right now is market validation. Some of our products have it, but given our youth, we’re still identifying our best markets. And personally, I’m only beginning to understand the complexities of managing people.

So far, I’m learning that aligning people to their strengths is essential. I’m guilty of getting frustrated by others for not sharing my strengths, but this frustration often arises when people are in roles misaligned with their abilities. Startups must be conservative with resources because we’re working with limited evidence, which equates to limited financial means. Until we demonstrate true value—defined relatively, as market value others prioritize over alternatives—we’re operating on degrees of faith.

Not all strengths are necessary at every stage of innovation, just as different strengths are needed in institutional processes. Expecting individuals to fully understand where they contribute best without support is unrealistic. I don’t know what an ideal economic system looks like to account for these differences. One emerging understanding is that traditional assumptions about rationality are incomplete. Behavioral economics illustrates how people often act irrationally, but beyond that, reason is constrained by time, resources, and individual factors. There is simply too much to know to make perfectly rational decisions about everything. And life happens in real-time, meaning even indecision allows the world to act on you.

I keep returning to the idea of the spectacle. I’m in my last semester of undergrad, seeing the light at the end of the tunnel of a college journey that I began in 2019. I took two years off in the middle, and during that break, I realized how many different ways of living exist and how personal timelines vary. Living within an imperfect system, I’ve come to believe that the best approach is to keep core values top of mind.

Step away from the noise of media, friends, family, and other influences, and listen to the anxious pushes and pulls inside. Then, align your actions with that self-understanding. Brands and status symbols only matter if you truly value them. The same goes for titles and achievements. It feels good to be admired and liked, but finding balance is something only you can determine for yourself. The spectacle is shiny, but it represents an average opinion. For many aspects of life, the average works, but rarely for the things that matter most. Only you can identify what those truly important things are for you.

WS founder Alex Tingiris shares his background and how it led to the foundations of our ambitious vision.

WS fosters collaboration, uniting remarkable individuals around shared values and emerging opportunities.